Esophageal Varices

Various systems are available for classifying esophageal varices. Unfortunately, they only overlap or coincide partly.

The official terminology used by the German Society for Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Verdauungs- und Stoffwechselkrankheiten, DGVS available on the DGVS website and the AWMF web site) is the Paquet classification (1). However, additional parameters are also directly included in it, such as:

- Number of strands

- Maximum diameter of the largest strand: less than or greater than 5 mm

- Location in the esophagus (distal, versus lower two-thirds, versus entire esophagus)

- Presence of what are known as red color signs — red patches, varices on varices (see below)

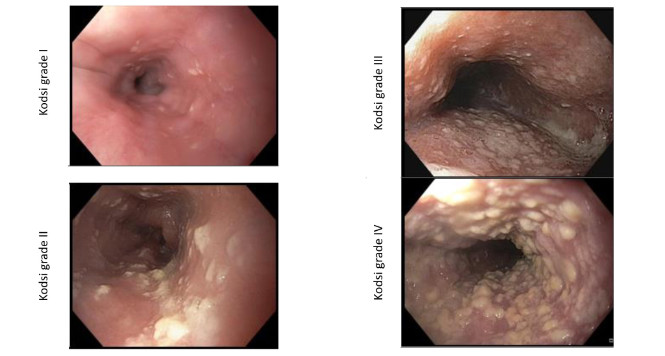

| Grade I | Varices extending just above the mucosal level | ||||

| Grade II | Varices projecting by one-third of the luminal diameter that cannot be compressed with air insufflation | ||||

| Grade III | Varices projecting up to 50% of the luminal diameter and in contact with each other | ||||

To classify varices, a “moderate” amount of insufflation of the lumen should preferably be used (although this leaves some scope for interpretation, of course). With low-grade varices (grade I), however, the disappearance of the varices on full insufflation should be tested (grade I).

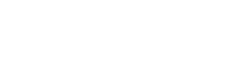

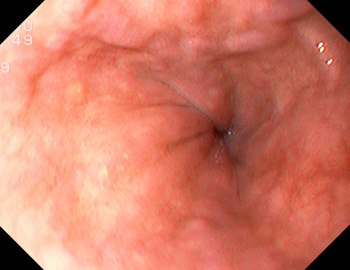

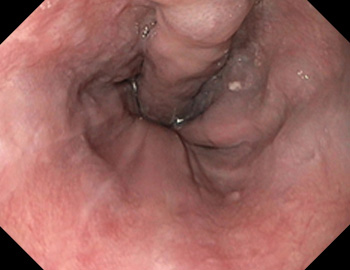

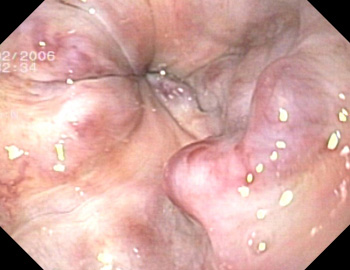

Examples of grade I

Varices extending just above the mucosal level and compression with air insufflation (lower row of images).

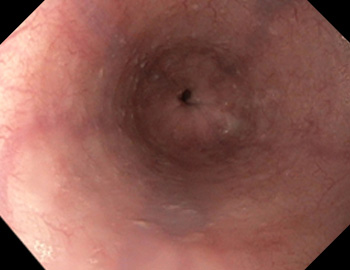

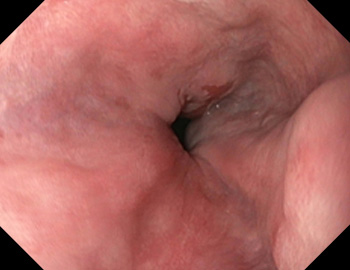

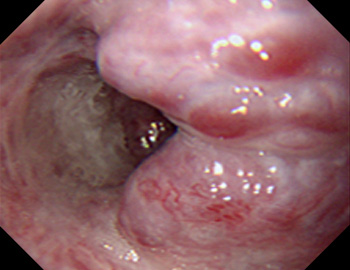

Examples of grade II

Varices extending above the mucosal level (with no compression when air is insufflated) up to one-third of the luminal diameter.

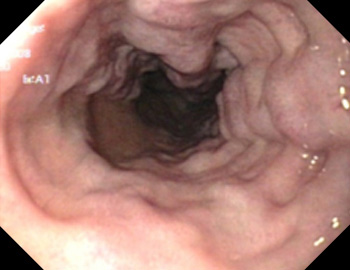

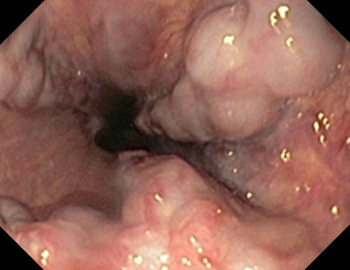

Examples of grade III

Varices extending for more than 50% of the luminal diameter, or touching.

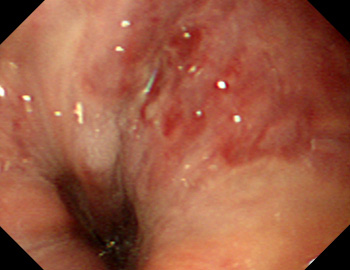

Examples of red signs

(also called red wale signs). These are red patches or strips on the varices, as a sign of an increased risk of bleeding, or of bleeding that has already taken place. Small varices lying on larger ones (varices on varices) are often considered to be among the risk signs. This category is sometimes also termed grade IV, although it is not included in the official Paquet classification.

Other classifications in the literature

JRSPH – The Japanese Research Society for Portal Hypertension classification(2) is as follows (with an increase in the risk of bleeding in each category, from top to bottom):

| Color | White Blue |

||||

| Red color sign | No/slight red wale markings/cherry red spots (A) Moderate/severe red wale markings/cherry red spots (B) |

||||

| Shape | Straight (F1) Enlarged, tortuous (F2) Very large varices (F3) |

||||

| Location | Lower third Middle third Upper third |

||||

These criteria are used to calculate a complicated score ranging from + 1.14 (risk of bleeding 0%) to –1.14 (risk of bleeding 100%), but this is probably too complicated to use in practice. Details on F1–3 and additional details on red color signs are occasionally given.

NIEC (North Italian Endoscopic Club) index (3) is based on the Japanese classification and uses three main parameters:

| Child Status | A/B/C | ||||

| Size of varices | Small / medium / large | ||||

| Red wale markings | None / mild / moderate / severe | ||||

This is used to calculate a complex points system,* which in turn is divided into six risk categories (< 20; 20–25; 25.1–30; 30.1–35; 35.1–40; > 40).

* Point scoring for Child status: A, 6.5; B, 13; C, 19.5; varix size small, 8.7; medium, 13.0; large, 17.4; red wale markings: none, 3.2; mild, 6.4; moderate, 9.6; severe, 12.8.

Dagradi (4)

| Grade 1 | Linear varices < 2 mm, reddish/blue, not raised on moderate insufflation, can be revealed by applying pressure with the endoscope | ||||

| Grade 2 | Blue, 2–3 mm, slightly tortuous, raised above the surface of the esophagus on moderate insufflation, sometimes also visible in the form of an “anterior sentinel vein” | ||||

| Grade 3 | Prominently elevated bluish veins, 3–4 mm, straight or tortuous, isolated distribution in the esophageal wall, “good mucosal coverage” | ||||

| Grade 4 | > 4 mm, circular extension around the esophageal wall; varices almost meet in the middle of the lumen; with or without “good mucosal coverage” | ||||

| Grade 5 | Racemose varices occluding the lumen, particularly marked with cherry red spots or varices on varices (“cherry red varices”) | ||||

Basic notes on the classifications

- Strictly speaking, the varix classifications only apply to the primary assessment, before (endoscopic) therapy. Classifications after treatment (e.g., with ligation or sclerosis) are more difficult; in this case, the (residual) varices should be described in terms of their number, location, and maximum diameter or red signs.

- In a comparative study (5), the Dagradi classification was found to have better sensitivity, but the two others (JRSPH, NIEC) had better specificity and a better positive predictive value. Since its introduction, the Paquet classification has not been validated in this way by other groups.

- Assessment variability: with the exception of one study that compared conventional and transnasal thin gastroscopy (6), most studies on this topic have shown only moderate values for interobserver variability — i.e., there were substantial variations in varix grading between different examiners, particularly in relation to the individual criteria (7–9). The studies concerned are already quite dated, but a more recent publication including children did not show substantially better results (10).

References

- Paquet, KJ. Prophylactic endoscopic sclerosing treatment of the esophageal wall in varices – A Prospective Controlled Randomized Trial. Endoscopy 1982; 14: 4–5

- Beppu K, Inokuchi K, Koyanagi N, Nakayama S, Sakata H, Kitano S, Kobayashi M. Prediction of variceal hemorrhage by esophageal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1981 Nov;27(4):213-8.

- North Italian Endoscopic Club for the Study and Treatment of Esophageal Varices. Prediction of the first variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and esophageal varices. A prospective multicenter study.N Engl J Med. 1988 Oct 13;319(15):983-9.

- Dagradi AE, Stempien SJ, Owens LK. Bleeding esophagogastric varices. An endoscopic study of 50 cases. Arch Surg. 1966 Jun;92(6):944-7.

- Rigo GP, Merighi A, Chahin NJ, Mastronardi M, Codeluppi PL, Ferrari A, Armocida C, Zanasi G, Cristani A, Cioni G, et al. A prospective study of the ability of three endoscopic classifications to predict hemorrhage from esophageal varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992 Jul-Aug;38(4):425-9.

- Pungpapong S, Keaveny A, Raimondo M, Dickson R, Woodward T, Harnois D, Wallace M. Accuracy and interobserver agreement of small-caliber vs. conventional esophagogastroduodenoscopy for evaluating esophageal varices. Endoscopy. 2007 Aug;39(8):673-80. Epub 2007 Jun 22.

- Bendtsen F, Skovgaard LT, Sørensen TI, Matzen P. Agreement among multiple observers on endoscopic diagnosis of esophageal varices before bleeding. Hepatology. 1990 Mar;11(3):341-7.

- Calès P, Buscail L, Bretagne JF, Champigneulle B, Bourbon P, Duclos B, Dapoigny M, Dumas R, Pierrugues R, Davion T, et al. Interobserver and intercenter agreement of gastro-esophageal endoscopic signs in cirrhosis. Results of a prospective multicenter study Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1989 Dec;13(12):967-73.

- Conn HO, Smith HW, Brodoff M: Observer Variation in the endoscopic diagnosis of esophageal varices. A prospective investigation of the diagnostic validity of esophagoscopy. N Engl J Med. 1965 Apr 22;272:830-4

- D’Antiga L, Betalli P, De Angelis P, Davenport M, Di Giorgio A, McKiernan PJ, McLin V, Ravelli P, Durmaz O, Talbotec C, Sturm E, Woynarowski M, Burroughs AK. Interobserver Agreement on Endoscopic Classification of Oesophageal Varices in Children: A Multicenter Study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015 Apr 15. [Epub ahead of print]