PPI, Aspirin and Prevention of Barrett’s Neoplasia – How Do We Treat Our Barrett Patients Now?

Thomas Rösch, Hamburg

Lancet 2018; 392: 400–08 Lancet 2018; 392: 400–08

| ORIGINAL ARTICLE Esomeprazole and aspirin in Barrett’s oesophagus (AspECT): a randomised factorial trial |

| Janusz A Z Jankowski, John de Caestecker, Sharon B Love, Gavin Reilly, Peter Watson, Scott Sanders, Yeng Ang, Danielle Morris, Pradeep Bhandari, Stephen Attwood, Krish Ragunath, Bashir Rameh, Grant Fullarton, Art Tucker, Ian Penman, Colin Rodgers, James Neale, Claire Brooks, Adelyn Wise, Stephen Jones, Nicholas Church, Michael Gibbons, David Johnston, Kishor Vaidya, Mark Anderson, Sherzad Balata, Gareth Davies, William Dickey, Andrew Goddard, Cathryn Edwards, Stephen Gore, Chris Haigh, Timothy Harding, Peter Isaacs, Lucina Jackson, Thomas Lee, Peik Loon Lim, Christopher Macdonald, Philip Mairs, James McLoughlin, David Monk, Andrew Murdock, Iain Murray, Sean Preston, Stirling Pugh, Howard Smart, Ashraf Soliman, John Todd, Graham Turner, Joy Worthingon, Rebecca Harrison, Hugh Barr, Paul Moayyedi |

Background

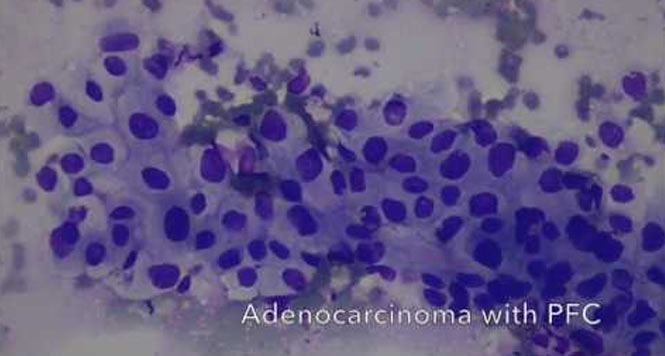

Oesophageal adenocarcinoma is the sixth most common cause of cancer death worldwide and Barrett’s oesophagus is the biggest risk factor. We aimed to evaluate the efficacy of high-dose esomeprazole proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) and aspirin for improving outcomes in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus.

Methods

The Aspirin and Esomeprazole Chemoprevention in Barrett’s metaplasia trial had a 2 × 2 factorial design and was done at 84 centres in the UK and one in Canada. Patients with Barrett’s oesophagus of 1 cm or more were randomised 1:1:1:1 using a computer-generated schedule held in a central trials unit to receive high-dose (40 mg twice-daily) or low-dose (20 mg once-daily) PPI, with or without aspirin (300 mg per day in the UK, 325 mg per day in Canada) for at least 8 years, in an unblinded manner. Reporting pathologists were masked to treatment allocation. The primary composite endpoint was time to all-cause mortality, oesophageal adenocarcinoma, or high-grade dysplasia, which was analysed with accelerated failure time modelling adjusted for minimisation factors (age, Barrett’s oesophagus length, intestinal metaplasia) in all patients in the intention-to-treat population. This trial is registered with EudraCT, number 2004-003836-77.

Findings

Between March 10, 2005 and March 1, 2009, 2557 patients were recruited. 705 patients were assigned to low-dose PPI and no aspirin, 704 to high-dose PPI and no aspirin, 571 to low-dose PPI and aspirin, and 577 to high-dose PPI and aspirin. Median follow-up and treatment duration was 8·9 years (IQR 8·2–9·8), and we collected 20 095 follow-up years and 99.9% of planned data. 313 primary events occurred. High-dose PPI (139 events in 1270 patients) was superior to low-dose PPI (174 events in 1265 patients; time ratio [TR] 1·27, 95% CI 1·01–1·58, p=0·038). Aspirin (127 events in 1138 patients) was not significantly better than no aspirin (154 events in 1142 patients; TR 1·24, 0·98–1·57, p=0·068). If patients using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were censored at the time of first use, aspirin was significantly better than no aspirin (TR 1·29, 1·01–1·66, p=0·043; n=2236). Combining high-dose PPI with aspirin had the strongest effect compared with low-dose PPI without aspirin (TR 1·59, 1·14–2·23, p=0·0068). The numbers needed to treat were 34 for PPI and 43 for aspirin. Only 28 (1%) participants reported study-treatment-related serious adverse events.

Interpretation

High-dose PPI and aspirin chemoprevention therapy, especially in combination, significantly and safely improved outcomes in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus.

What you should know about this paper

Almost everybody prescribes at least low-dose PPI to their Barrett patients even if they complete asymptomatic – is this warranted? The AspECT trial tries to answer this question, a task that cannot be praised enough1. The fact that clinical researchers have undergone the pain of a “boring” clinical study of this magnitude with medications in use for an eternity, must be highly recommended and should be an example for clinical research funding in many countries that focus and spend all or most of their money on basic and so-called translational research. Nevertheless, are we allowed to disagree with the conclusions of this paper? Shall we recommend PPI high-dose plus aspirin to our Barrett patients now? The authors of a brief concomitant editorial remain hesitant2.

The study shows a small, but overall survival benefit for Barrett patients on high-dose PPI (i.e. 40 mg, p=0.04), which was slightly increased when adding aspirin, but only when results were corrected for those taking NSAIDs (p=0.007). So far, so good. But this benefit was probably not due to prevention of cancers in Barrett’s esophagus, but may be due to other factors. In a very careful previous analysis of the literature3,4, the authors could not find a consistent preventive effect of PPI or low-dose aspirin, which made them start the present trial. It must be said that case number calculation was halved from 5000 to about 2500 in the middle of the trial – due to new data appearing – in exchange for a longer follow-up (intended 10 years instead of 5 years), which can be debated.

Nevertheless, there was only a significant effect on overall survival, not on development of Barrett’s neoplasia (or probably death from it). It has to do with the definition of endpoint and possible differences, as the data from the paper and the online addendum with additional data show:

| PPI HD vs. | PPI ND | p | ASS vs. | kein ASS | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause mortality | 79/1270 | 105/1265 | 0.039 | 73/1138 | 90/1142 | 0.16 |

| Adeno-Ca Barrett | 40/1270 | 41/1265 | 0.86 | 35/1138 | 35/1142 | 0.92 |

| HGIN Barrett | 44/1270 | 59/1270 | 0.12 | 37/1138 | 55/1142 | 0.053 |

| LGIN at baseline | 29/1270 | 42/1265 | ? | 25/1138 | 46/1142 | ? |

| Specific mortality | 8/1270 | 12/1265 | 0.34 | 8/1138 | 8/1142 | 0.98 |

HD high dose, 40 mg, LD low dose 20 mg. ASS in doses of 300 mg in UK and 325 mg in Canada.

HGIN high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (dysplasia), LGIN low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (dysplasia)

There appear to be fewer HGIN cases in the high dose PPI and in the ASS groups: both these differences are statistically not significant, the latter just failed to reach significance (p=0.053). For this HGIN group, it could be speculated that there was a higher a priori risk mirrored by a higher LGIN rate at baseline, which then led by progression to also a higher HGIN rate in these arms. However, first of all, not significant is not significant and not too much should be speculated based on “trends”. Secondly, as a further limitation, only HGIN and cancer, but no LGIN cases were reviewed by a second histopathologist in the study, and we know very well that most LGIN diagnoses are not confirmed by a second opinion/expert opinion5–7.

What about mortality? Comparing all-cause mortality and specific (cancer-specific) mortality in the table shown above, high-dose PPI has a significant effect only on all-cause mortality. Subtracting specific mortality (8 vs 12 cases, not significant), there remains a non-Barrett-related mortality rate of 5.6% (71/1270) versus 7.4% (93/1265) for high- versus low-dose PPI. We do not learn whether this difference was also significant or not, so the final answer is open – does high-dose PPI plus ASS have an effect on overall mortality mostly via other factors than cancer prevention? At this stage, the floor should be open to good clinical statisticians.

In conclusion, this laudable and large randomized trial shows that high-dose PPI plus ASS has some overall effect on mortality in Barrett patients, but mostly not by any significant effect on cancer prevention. It is currently open whether a further study – which should be even larger – will follow to answer this question. A general recommendation for high-dose PPI plus ASS in Barrett patients for cancer prevention, however, appears unfortunately to be premature.

References

- Jankowski JAZ, de Caestecker J, Love SB, et al. Esomeprazole and aspirin in Barrett’s oesophagus (AspECT): a randomised factorial trial. Lancet 2018;392:400-8.

- Hvid-Jensen F, Drewes AM. Should aspirin and PPIs be recommended for patients with Barrett’s oesophagus? Lancet 2018;392:362-4.

- Bennett C, Moayyedi P, Corley DA, et al. BOB CAT: A Large-Scale Review and Delphi Consensus for Management of Barrett’s Esophagus With No Dysplasia, Indefinite for, or Low-Grade Dysplasia. The American journal of gastroenterology 2015;110:662-82; quiz 83.

- Bennett C, Moayyedi P, Corley DA, et al. Addendum: BOB CAT: A Large-Scale Review and Delphi Consensus for Management of Barrett’s Esophagus With No Dysplasia, Indefinite for, or Low-Grade Dysplasia. The American journal of gastroenterology 2015;110:943.

- Duits LC, van der Wel MJ, Cotton CC, et al. Patients With Barrett’s Esophagus and Confirmed Persistent Low-Grade Dysplasia Are at Increased Risk for Progression to Neoplasia. Gastroenterology 2017;152:993-1001.e1.

- Duits LC, Phoa KN, Curvers WL, et al. Barrett’s oesophagus patients with low-grade dysplasia can be accurately risk-stratified after histological review by an expert pathology panel. Gut 2015;64:700-6.

- Curvers WL, ten Kate FJ, Krishnadath KK, et al. Low-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: overdiagnosed and underestimated. The American journal of gastroenterology 2010;105:1523-30.